I leant against the low wall around the edge of the roof and looked out across Delhi. In the evening light I could just begin to make out the glow from cooking fires of families living alongside Loni Rd. High above them black kites wheeled through the smog. There were always so many of these birds in the sky here.

Was I crazy? I wondered. I was about to lead a Buddhist practice session here and I had lost faith in the teachings that I was supposed to be offering. Should I be saying anything at all?

It was 2007 or 2008. In a few minutes a group of local Buddhists would arrive. Most of them would have walked a couple of miles to get here, from just over the state border between Delhi and the poorer state of Uttar Pradesh. They were Dalits, low-caste Indians that had converted to Buddhism following the example of Dr Ambedkar.

Our Buddhist communities had met while mine was teaching English out here, at the suggestion of an Indian monk we had met in the UK. “Our communities need help” he had said.

“What can we do?” we asked.

“Teach English.”

As our volunteers got to know people they explained about their lack of access to Buddhist teachings and places to practice.

“Could you help with that?” they asked, “Can you offer a space for Buddhist practice and share some Pure Land teachings with us?”

We figured out a way forward together. The ultimate goal was to support some of the people here to lead practice sessions within their own communities.

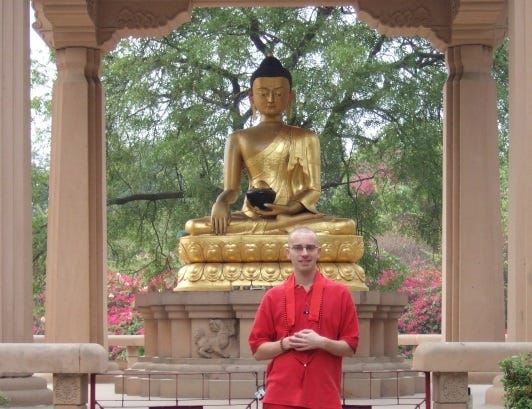

That all happened before I joined the project. I went out to support with the Buddhist side of things, although I helped out with the English classes when I could.

We rented a room on this rooftop to use as our temple, above the flat I was staying in. I went inside and began to light the candles. I could hear the neighbour’s television, an argument from another flat somewhere in the building, children playing in the park below, and the quiet noise of traffic in the distance.

Once a week we would meet here on the rooftop. On other days I would travel out to different parts of Uttar Pradesh and Delhi and we’d practice together in their homes.

This was the first time during this visit that I had met everyone here.

People began to arrive and sit down cross legged on our meditation cushions. It was a small room and we filled the space. It was hot. My shirt stuck to my back with sweat. We had to keep the fan turned off otherwise it would blow the candles out. I kneeled in front of the shrine and lit a stick of incense.

“Am I doing the right thing?” I asked myself, “being here while carrying a crisis of faith in my heart?”

But tonight something magical would happen.

A few weeks earlier, when I was confessing to a mentor that my faith had collapsed, I couldn’t have imagined what this evening in our rooftop shrine room would bring.

I looked at the Buddha on the mantelpiece; I looked at the textured wallpaper and at the ornate light fitting. I looked out of the window. Occasionally I looked at Caroline.

This was England, a few weeks earlier. I had asked if we could have a chat.

I had been reading and listening to such a wide variety of teachings, both from within Pure Land and from across the whole of Buddhism. So much seemed to contradict each other. One teacher would say that it’s like this. Then another teacher would say the opposite. How could anything being trustworthy? I was sure that none of it was.

I told Caroline how I felt.

She nodded and smiled. She didn’t seem surprised. Having doubts and questions is not just understandable but an essential part of the spiritual life.

The teachings of Pure Land Buddhism had just stopped making sense to me. Was the Pure Land in this world or the next world? I didn’t believe in life after death but if the Pure Land was here and now how to explain suffering? And there was so much suffering…

She didn’t try to answer or my questions, or solve my crisis. She just accepted that this was where I was right now. I appreciated that.

Was Buddhism right for me? I was convinced that it wasn’t.

“What will you do about India?” Caroline asked.

That question stopped me in my tracks. What was I going to do? I was due to go out and support our Indian friends with their Buddhist practice. Part of that would be offering teachings and practice sessions.

Doing what I say I’ll do is such an important value to me. But so is speaking truthfully. Could I go and speak about this crisis of faith? I was worried that I would undermine their faith. And I was very fond of the people in that community. What was I going to do?

Suddenly there was a moment of clarity. I had not worked the answer out. But a clear view of the right path arrived.

“I will go and do what I said I would do.” I replied. “I will go and tell the stories of Pure Land Buddhism, and offer practice spaces, and share what I have learnt.” That’s what my Indian friends were asking for, and I knew I could do that even if I was carrying my own private doubt.

It didn’t quite make rational sense. Why share something that I no longer had any confidence in? Nevertheless my heart was set. I packed my suitcase, and I packed up my doubt.

I guess I wasn’t as convinced that Buddhism was as useless as I was telling myself.

The daylight had quickly gone from the sky. The windows in our rooftop shrine room showed only darkness.

We chanted the three refuges and lay precepts together in Pali and Sanskrit, and then we settled into silent meditation.

“Here is my questioning mind.” I noticed, “Here is my breath.”

“Here is my anxiety about my future in Buddhism.”

“Here’s my breath.”

“Here’s my strong desire for the world to make sense.”

“Here’s my breath.”

“Here’s how unsafe things feel when I can’t explain them.”

“Here’s my breath.”

Suvidya rang the bell to mark the end of meditation. We bowed to each other, and began to chant the nembutsu.

We wouldn’t have won any prizes for being tuneful, and yet it was the most beautiful thing I had ever heard.

I opened my eyes and looked at the faces around me, lit up by the soft orange glow of flickering candles.

The present moment was perfect in its imperfection. There was nothing I wanted to add and nothing I wanted to take away. Not the smog. Not the tunelessness. Not the sound of the TV from our neighbour.

Here was another moment of clarity.

In that moment I was experiencing the Pure Land: these people I was chanting with, the candles, the incense, the noise, the heat; all of it.

The teachings were just pointers, I realised, pointers to this experience. A knowing that goes beyond words and can’t be fully captured by them. Of course the teachings will be contradictory, how could they not be.

The question of where is the Pure Land was also answered by that experience, it was not answered for good, but in that moment knowing I was in the presence of the Pure Land right then was enough for me.

The question of suffering was also answered, although not directly. I saw that my desperation with that question came not from a longing for doctrinal straightforwardness but from simply wanting to avoid suffering. And as the Buddha said in his first sermon, suffering cannot be avoided.

I was filled with gratitude for the community around me in that moment, for Caroline listening to me back in England, for all the conditions that had led to me being here.

The chanting faded to silence and we sat in the presence of one another, and in the presence of the Pure Land.

Wonderful Kaspa! I'm a bit sorry that it's taken me ten days to read this and read it again. Two things jumped out at me. The first is that teachers are the pointers, and don't necessarily have to embody the teaching to be effective in their role. The second is that doubt is a valid and expected(?) part of one's spiritual journey. I am feeling less defeated by doubt and more able to recognize it for what it is, and move curiously past it. Thank you! Love, Virg.

Quite lovely! 🙏🏽